(EDITOR'S NOTE -- You may remember Percy Shelley's dusty voice boasting from the grave: "My name is

Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!" Ozymandias never looked on Nekoma,

N.D. Should he, he might well tug on his beard in wonderment, if not despair.)

By Sid Moody, AP Newsfeatures Writer (24 January 1981)

NEKOMA, N.D. -- What makes this wheatland hamlet different is a mammoth topless pyramid out in the

snowblown stubble of the prairie big enough to stow a whole dynasty of pharaohs in if there were any pharaohs

around, which there aren't.

In fact, all that's inside the pyramid now is 18 feet of leaking water and all the pipes and wires Buford

Faust didn't have time to pull out of it before it was welded shut.

Nonetheless, as with all proper pyramids, this one is a tomb of sorts -- a tomb of a fallen warrior, the

tomb of the ABM, the antiballistic missile of great controversy a scant decade ago.

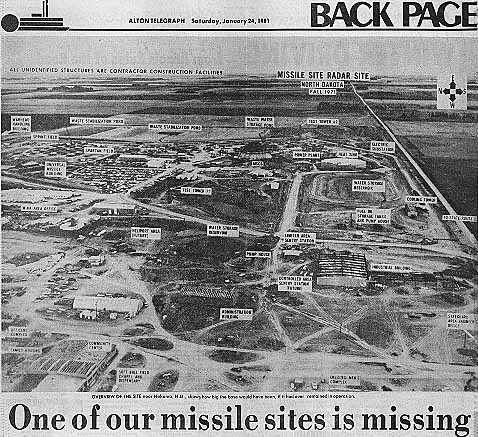

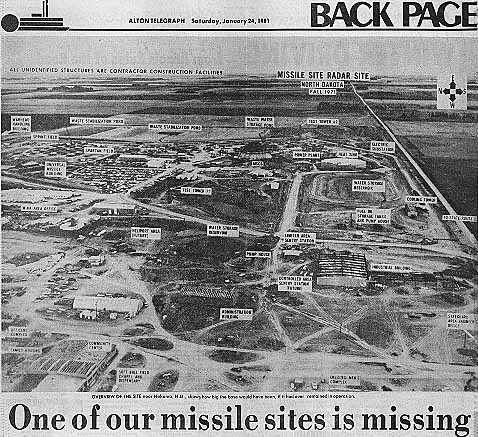

The pyramid is a survivor of 102 holes the Pentagon dug hereabouts into which it poured 5.7 billion of

your tax dollars. One hundred of the holes held missiles. The pyramid held radar and computers and push-buttons

and such and was designed to survive ought but a direct atomic right to the jaw. Even the toilets were

shock mounted.

Four months and 10 days after it all went operational in 1975 the Pentagon shut it down and began moving

everything out. The visible remains tody are a radar in the 102nd hole that can spot a beer can at 800 miles

and Nekoma's pyramid, which will undoubtedly still be standing when the next Ice Age is remembered as a

brief cold snap.

Something as conspicuous as the pyramid, a 75-foot replica of the one on the back of a dollar

bill, visible for miles across the flatlands, is a literally concrete object lesson for those who would know

something about Cold Wars, megaton trolley lines trundling MX missiles beneath the Great Basin of Nevada and

Utah, the accuracy of top brass predictions, and a few sidelights about a distinct breed of people who call

themselves NoDaks.

Nekoma, to be fair, doesn't look like Atlanta after Sherman. But there are evidences the Pentagon marched

through bringing boom, and left, leaving bust. Stores stand empty like an abandoned movie set. Only a pickup

truck or two belly up in front of the Nekoma Bar, where hundreds used to be. The school yard is deserted.

People still live in the low-slung houses that duck from the cold. But there are probably more souls in St.

Edward's Cemetery, at the other end of Main Street from the grain elevator, than in town.

Beyond the cemetery is a brand new community of missile base houses, discarded as an old boot. And, to

the east of that, the pyramid.

Nonetheless, life goes on. The NoDaks didn't get so greedy that they lost their

perspective -- or shirts. Quite a few wouldn't mind another boom. They miss the excitement. But they've

learned a lot.

To see how Nekoma got to where it is today, let's start in the newspaper files in Grand Forks.

They recall the battle in 1969 when Safeguard, as the ABM was then known, was if anything more hotly fought

over than the MX is today. It squeaked through the Senate by one vote, that cast by Vice President Spiro Agnew.

There's a clip of Lt. Gen. G.V. Underwood, commander of the U.S. Air Defense Command, addressing a

luncheon right in Grand Forks: "Safeguard compares in importance to the Manhattan Project." In 1971

there's President Nixon: "(The ABM) is the most important element in our nation's security."

There's also Sen. George McGovern: "The most blatant boondoggle ever pawned off in the name of national

defense." And there's Sen. Henry "Scoop" Jackson who asked, assuming Safeguard's 100 missiles successfully kayo

a warhead, what happens when the Russians send over a 101st?

In large part, the logic of this is what eventually kayoed Safeguard.

In the meantime, however, Cavalier County, N.D., to which Nekoma contributed 82 souls in the 1970 census,

had a missile boom. Cavalier County is one of the unsung nuclear powers on Earth. There are 32 remotely fired,

multiple-warhead Minutemen missiles buried beneath the amber waves of durum

wheat -- the stuff they make pasta of -- and barley -- the stuff they make malt out of, a high proportion of

which, one must conclude, is consumed locally.

The NoDaks of Cavalier County are Cold War veterans. A hundred more missiles didn't rile them unduly.

They are survivors. Of Indians of yore and of always and forever drought, flood, grasshoppers, tornadoes,

wheat prices in Minneapolis, regulations in Washington and a winter wind that only a yak could love.

Let us move on to the present, to the Nekoma Bar where wheat farmers wait for the ground to thaw in the

unlikelihood of spring by consuming malt and other grain derivatives they have grown in prior years. The

proprietor is Bill Verwey who is also Nekoma's mayor, probably for life. He's an ex-paratrooper who was in

MacArthur's honor guard when the general landed in Japan to do the country over, former operator of the grain

elevator until the uncertainties of that high-risk crap shoot ate at his stomach, and husband of Nekoma's

police force.

Lenora Verwey got the job when her predecessor, Alfred Duerr, feared he wasn't up to policing

a missile boom. Verwey attributes his model citizenship to his wife's constituted authority. Hizzonor thinks

Lenora's badge is in a desk drawer over at Tony Lieberbach's house, but he can't say for sure. Tony is the town

water department, overseeing the brand new system the government put in after Nekoma's population swelled to over

200. Before that the town subsisted on alkaline mud.

Nekoma had a pretty good boom. Grain has always been the area's meat and potatoes, so the ABM with its

$35 million annual construction payroll was gravy. The farmers plowed on, seeding around all the holes.

In Langdon, the county seat 10 miles up the road towards Canada, the population ballooned from

2,182 to a peak of 4,600. Trailer courts sprouted like winter wheat. Prices edged up, too, but locals say they

were so far behind to start with it was just a matter of catching up with the rest of the world. And of course

the well went dry.

Dr. Harold "Doc" Blanchard, the town's cheery chiropractor and mayor, got a call one evening from a man

in a bar complaining there was no water for his whiskey. The mayor apologized and invited him over for a shower.

The NoDaks are like that: friendly. You can sit in the Mecca Lounge on the edge of Nekoma with three strangers,

and before you can sample your first malt, there are three more in front of you.

The NoDaks loved the boom and the boomers, and when it was over, they started up the combine and went

back to "thrashing."

Oh, Bill Verwey bulldozed a trench across Main Street to keep the one peace march Nekoma experienced

out of town. But there was also so much gravy he had to pass an ordinance to allow parking in the middle

of Main Street, a thoroughfare as wide as the New Jersey Turnpike.

In Langdon, the schools were bursting at the blackboards, but NoDaks being NoDaks the high

school cheerleaders made sure one of the new girls was picked every year to be a pom-pommer. Friendly.

NoDaks know better than most that every flood has its famine, but hadn't the Pentagon kept saying there

would be 4,000 permanent personnel manning the missiles? If any doubted, there was always another Washington

bigwig up to tour the site -- "everyone but Nixon himself." The money kept coming -- $137 million just to build

pyramids, silos and the Stanley R. Michelsen (sic) antimissile base complete with chapel, PX, barracks, gas

station, bowling alleys, tennis courts and 200 houses with 200 more to come. Military wives complained to Mrs.

Creighton Abrams, wife of the Army chief of staff, during a visit that they were getting blizzarded on walking

outside to the commissary. The government built a $20,000 breezeway.

Although there were a few clouds on the horizon -- the 1972 SALT agreement with Russia limited the United

States to two ABM sites, Nekoma and Washington -- systems remained "go." Six diesel generators big enough to

power half of North Dakota were moved into the pyramid. Electricians spent months, years, threading computer

wires among the shock springs, concrete and lead shielding.

"I should have known when they flew up an Army band to dedicate the base. That was late '74. We could

have used the high school band just as well," says Blanchard. "I thought, 'What a waste.' I had a few more days

left of innocence."

About a year, actually. The mayor spent part of it anteing up his share of $81,000 for gas

improvements in a trailer court partnership. That should be proof enough, he says, that no one in Cavalier County

knew what was coming, that they took the government at its word.

The base went fully operational -- all missiles in place, the radar radaring,

the tennis courts tennising -- on schedule Oct. 1, 1975. The next day the House voted 353-61 to adopt the

federal budget calling for the base to be deactivated. A Pentagon order made it official Feb. 10, 1976.

Terry Phelps, then the General Motors agency manager, suddenly found himself with a building twice

as big as he would need. Jim Allbrooks, a career Air Force man who had come up with the construction crews,

found himself with his brand new Mecca Lounge with its palm tree sign, an ironic accompaniment to the nearby

Nekoma pyramid. Blanchard found his trailer court deserted and his town with two cops too many, an unused new

hospital wing and a brand new water system twice as big as needed.

"You could say we're overserviced," he says today.

In Nekoma, the new school is closed -- Verwey hopes a waffle maker

might take it over -- the two gas stations ditto, the bank ditto, the B and L grocery ditto, everything ditto

except Verwey's and Allbrook's bars, the elevator and the post office. Population is about back to what it was

10 years ago here and in Langdon.

"They say when you lose your school, a town dies," Verwey philosophizes. "I say as long as you got a bar,

you'll survive."

What pulled the plug? SALT, for one. The Washington ABM site was never on more than paper. A third one in

Montana was stopped by the treaty when 8 percent completed. It cost $1 million just to blow up their pyramid and

cart it away. There was no question the ABMs could do their job. Tests proved it. But meanwhile, the Russians

had refined their miltiple-warhead technology to the point where Scoop Jackson's question had become a reality.

The 101st warhead. In a sense, Nekoma had been a Cold War bargaining chip, and the game had changed.

"It seems like a lot of money to put into a card game with the Russians," says then-mayor Leon DuBourt of

Walhalla near where the ABM long range radar still operates looking at satellites.

Outback near where the birds of war once roosted in their silos, the YACC kids are raising

pheasants. One night a week the bowling alleys and gym are opened to the public, admission $1. What will ever

become of the houses has not been determined -- they stand in neat rows like steadfast soldiers complete with

playgrounds and empty mailboxes and are, incredibly for a visitor from the urban East, untouched by vandals or

graffiti. But YACC has kept the Stanley R. Michelsen (sic) base not a total waste.

On the other hand, Doc Blanchard has only an empty trailer court, a white hard-hat and a ceremonial

chrome-plated shovel to show for it all.

"I think the resistance in Congress to the MX is like it was with the ABM. But the dollar commitments

are made to design and build the hardware, so projects like this take on a life of their own. I'd tell any

mayors in Utah or Nevada to look gift missiles in the mouth. You can't help but be skeptical."

There are also skeptics who wonder how many colonels made generals' stars by devotion to a missile

system that had a life of its own.

Not that the NoDaks feel left naked to their enemies. The Minutemen are still there, lurking along the

roadsides. Linda Simon, a young farm wife, pondered between pool shots at the Mecca one recent Saturday night

when the nations of the world "are going to stop acting like second graders" building ever bigger and better

megabangs. But Cavalier County by and large believes in the need for rocketry.

"No missiles, no wheat farmers," says Don Green, hoping nonetheless Washington feels it has an

obligation to help YACC kids as well as plant rockets.

But the NoDaks today are more apt to talk about the new pasta plant in Cando, an aptly named

community farther west, than missiles. Noodles by Leonardi finally came around to the bright idea that it might

be better to take the mill to the grain rather than the grain to the mill. That's technology NoDaks can

empathize with.

What to do with the pyramid is something else. One promoter suggested putting a neon sign atop it and

making Nekoma the Las Vegas of the north. Certainly it's too flooded to store grain in. Bill Verwey has received

tons of mail asking about the houses, but they aren't his to dispose of.

He doesn't regret the boom. "It got me into the bar business," he reflects, having found it more restful

loading friends and neighbors than grain elevators. Another boom might get all Nekoma's streets paved instead of

just the one leading to the school.

"I could have blacktopped the whole town for what the government spent on one road, but they insisted on

doing it their way. But I suppose the majority likes things as they are now."

There's still enough talent in town that his fast pitch softball team made the state finals last summer.

But there's nothing to keep the young in town, not even a school now.

He trundles off to the beer cooler beneath a poster that proclaims: "Great beer bellies are

made, not born."

He delivers another load to fulfill the declaration and ponders the pyramid.

"I guess it was all a terrible waste. But if you don't get smarter, there's no sense getting up in the

morning."